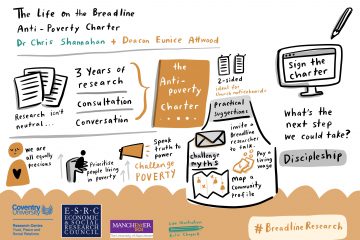

Poverty in the UK continues to rise, making it more important than ever to understand lived experiences of poverty. Life on the Breadline researcher, Stephanie Denning, has recently published a paper in the journal Antipode that responds to a gap in understanding collective experiences of poverty by analysing the atmospheres at three foodbanks in two British cities in 2014 and 2019.

To do this, the paper engages with capacities of clients and volunteers at the foodbanks – the capacity of clients to be in a situation different to that of their current experience of poverty, and the capacity of foodbank volunteers and managers in terms of how they desired the foodbanks to be run.

This blog post summaries the key arguments of the paper. Overall, the paper argues that the atmospheres at the foodbanks were formed by an ever-changing relationship between these capacities through the past, present, and anticipated future, and the ongoing context of austerity.

Foodbanks and austerity in the UK

Austerity in the UK is contested both politically and in how it is defined. In our Life on the Breadline research we have followed economic geographer Sarah Marie Hall’s understanding of austerity: austerity is both an economic state policy to reduce government public spending in order to reduce the government’s budget deficit, and a lived experience in people’s daily lives. To see some of the key austerity policies over the last decade, visit the Life on the Breadline austerity timeline.

Researching foodbanks

The paper is based on ethnographies at three Trussell Trust foodbanks: two foodbanks in Bristol in 2014 (North Bristol Foodbank and Bristol North-West Foodbank), and one foodbank in Birmingham in 2019 (B30 Foodbank).

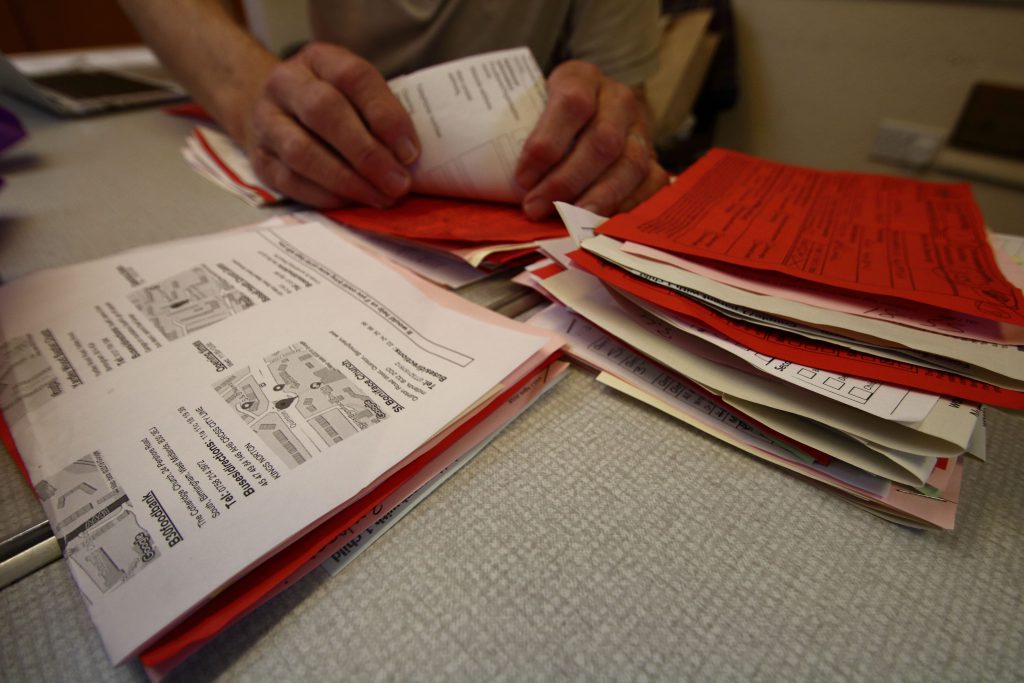

Like all Trussell Trust foodbanks, the foodbanks required people coming to the foodbank for food to have a voucher issued by a referral agency. Clients received three days’ worth of predominantly non-perishable food to take home, and officially could only use the foodbank three times in any six month period.

The ethnographies all involved Stephanie spending time at the foodbanks, getting to know volunteers, chatting with clients, and on occasion helping with paperwork and packing bags of food. Interviews, questionnaires, and a focus group were conducted with volunteers and clients.

Atmospheres at the foodbanks

The paper examines atmospheres through the concept of capacities with the philosopher Spinoza – a capacity is about the power of a human body to act, so refers to what they can and cannot do. The thematic analysis of the data from the foodbanks drew out capacities – and resulting atmospheres – in two main ways: the capacity of clients to be in a situation different to that of their current experience of poverty; and the capacity of foodbank volunteers and managers in terms of how they desire the foodbank to be run.

Clients

At all of the foodbanks I met clients who had not eaten, including parents who had skipped meals to give food to their children. Therefore, the foodbanks changed clients’ capacities by giving food:

I have to rely on the foodbank to keep me going for the next couple of days until I do get paid and it’s just one big struggle after another.

(Client, B30 Foodbank, 2019)

For some clients this resulted in gratitude, relief, and a change in mood:

Many times [I have] come here on the verge of tears and left with a smile.

(Client, Bristol North-West Foodbank, 2014)

This client, like others who I met, gained some hope from being at the foodbank that their current situation could be different in the future. This could result in a positive atmosphere at the foodbank, but whilst important, it would be overly simplistic to stop here…

Whilst the foodbanks officially provided emergency food provision, the clients that I met were increasingly in situations of ongoing poverty which affected their capacities daily:

It’s quite depressing to see… being here today and I’m not the only one here, and looking at people they look drawn, tired, helpless, shouldn’t be living like that they shouldn’t. That’s the effect it has on me, just seeing the whole world falling apart daily… it’s hard when you look in the cupboards and there’s nothing there.

(Client, B30 Foodbank, 2019)

By 2019, the clients who I met were increasingly affected by austerity, and in particular benefit cuts and the introduction of Universal Credit. For many clients, their experience of hunger therefore stretched from the past into the present and the anticipated future which negatively affected their capacities and in turn affected the atmospheres at the foodbank through the visible sense of people’s need.

Overall, clients’ capacities – and therefore the atmospheres at the foodbanks – were affected by whether clients could envisage a different future to the conditions in which they were currently living. Whilst not all of the foodbank clients were recipients of state benefits, the progression of austerity affected their future (particularly Universal Credit), and so as austerity measures progressed the atmospheres around the possibility for a more positive future became less certain.

Volunteers

To some extent volunteers had the most control over the atmospheres at the foodbanks, for example in fundamentally wanting to respond to people’s need through giving food, and by designing the physical environment of the foodbanks with the aim of showing care with tables and chairs in a café style, often with tablecloths and the offer for clients of a hot drink. However, this could not entirely counteract the stigma that some clients felt on entering the foodbanks:

I heard a client being introduced to a volunteer who asked if she would like a hot drink. The client replied “No, I just want to get out of here” and the volunteer led her through to the church and tried to reassure and calm the client.

(Stephanie’s diary, B30 Foodbank, 2019)

Whilst the client needed food, they did not want to be at the foodbank, and there was conflict between the volunteer aiming to offer comfort, and the client feeling uncomfortable. Indeed, atmospheres at the foodbanks were transient, and so whilst I reflect on dominant atmospheres, the atmosphere could also change in an instance.

In varying regards the foodbanks were affected by a Christian ethos. The Trussell Trust is a charity that is based on, shaped, and guided by Christian values but through its social franchise model the Bristol and Birmingham foodbanks each had a level of independence meaning that the explicitly Christian element of the foodbanks and the degree to which this affected the atmospheres varied.

In Bristol the foodbanks were run by churches and had Christian managers who spoke of their Christian faith motivating them to respond to poverty by establishing the foodbanks. It was not a requirement to be Christian to volunteer, but the majority of Bristol volunteers were Christian, and at several outlets volunteers offered to pray with clients although this was not a requirement for receiving food. The manager of Bristol North-West Foodbank explained the Christian element:

So we don’t hide it [being Christian] but it’s just part of, it’s woven in. And I think people, it depends how open they are, I just hope they all feel equally respected and cared for while they are here really.

(Manager, Bristol North-West Foodbank, 2014)

By contrast, at B30 Foodbank in Birmingham, whilst it ran in a church the volunteers and management team were a mix of Christians and people who were atheist or agnostic, and several volunteers specifically told me that they were not like other foodbanks where people prayed with the clients. Despite this, one volunteer who was an atheist shared:

But the ethics of Christianity, you can’t deny and that’s what we are trying to live to. And this is true Christianity in operation.

(George, volunteer, B30 Foodbank, 2019)

The Christian ethos therefore affected the atmospheres at the foodbanks in multiple ways, but overall related to the aspiration for an ethos of care.

Finally, the atmospheres at the foodbanks were affected by volunteers in terms of how they managed foodbank resources; both food and time. The national Trussell Trust statistics show the increase in foodbank use: over 1.2 million food parcels 2015-2016 and over 1.9 million food parcels 2019-2020, with this figure increasing further over the Covid-19 pandemic. During my time at the Bristol foodbanks in 2014, they were busy but there was enough food to meet demand, and time for volunteers to sit and chat with clients over cups of tea. In 2014 in Bristol it had been notable to write in my diary that a client had arrived before the foodbank opened yet five years later at B30 Foodbank I wrote:

As I now know to be normal, there were already people sat waiting in the entrance hall to the church when I arrived over 30 minutes before the foodbank opened.

(Stephanie’s diary, B30 Foodbank, 2019)

Physical capacity at the foodbanks therefore centred on a balance between the number of people receiving food and available resources; food, volunteers, and time. The fallout from this balance affected the B30 Foodbank atmosphere by remembering a less busy past compared to the present as it became more rushed, signposting was more difficult, and clients had to wait longer for food.

Overall, whilst it might be expected that the foodbank managers and volunteers had the greatest control over the atmospheres at the foodbanks through their desire for how the foodbank would run around a Christian ethos, care, and a desire to help people in need, such control was not obtainable. This is because whilst volunteers’ capacities did significantly affect the atmospheres at the foodbanks, their capacities were inherently relational to the capacities of clients and to the wider context of austerity and welfare cuts which each in turn affected the overall atmospheres at the foodbanks.

Conclusions

Overall, atmospheres provide a means to explore collective experiences at foodbanks, and therefore collective experiences of poverty. Based on ethnographies at three foodbanks in 2014 and 2019, analysis has found that the foodbank atmospheres were affected by the capacity of clients and of volunteers, with none of the volunteers who I met also being foodbank clients – austerity and poverty have not affected society in the UK equally.

Exploring atmospheres in terms of capacity drew out how the foodbank atmospheres were affected by the capacity of clients to be in a situation different to that of their current situation; and secondly the capacity of foodbank volunteers and managers in terms of how they desired the foodbanks to run. Time was important here as the atmospheres were affected by capacities in the past, present, and anticipated future of clients and volunteers at the foodbanks. This is a double adverse impact in terms of lived experiences of poverty and austerity: the foodbank atmospheres were not only formed in the present but were also affected by people’s past experiences of poverty and their fears of future poverty as austerity measures became harsher and it became harder to imagine a more positive future.

Interested to know more? The full paper is available to read (open access – free to read) in the journal Antipode through this link.