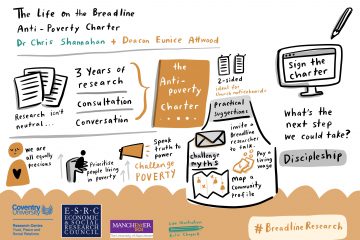

On 23rd June 2020 at the online ENUF UK conference on food and poverty we hosted a workshop ‘Questioning the role of religious faith in UK food provision’.

In this blog post we – Stephanie Denning (Coventry University, Life on the Breadline), Andy Williams (Cardiff University), Maddy Power (University of York), Charlie Pemberton (Durham University), and Phil Cullen (independent researcher with Church Action on Poverty and the Catholic Centre for Social Thought and Practice) – share some of the key conversations from our workshop:

The workshop opened with three key questions:

- Do faith motivations help or hinder progressive approaches to food insecurity?

- How might religious responses to food security be exclusionary or unethical?

- Can religion offer a radical vision of food justice?

We addressed these questions through three themes: motivations, practices, and political theologies of food justice.

Motivations

Reflections from Stephanie:

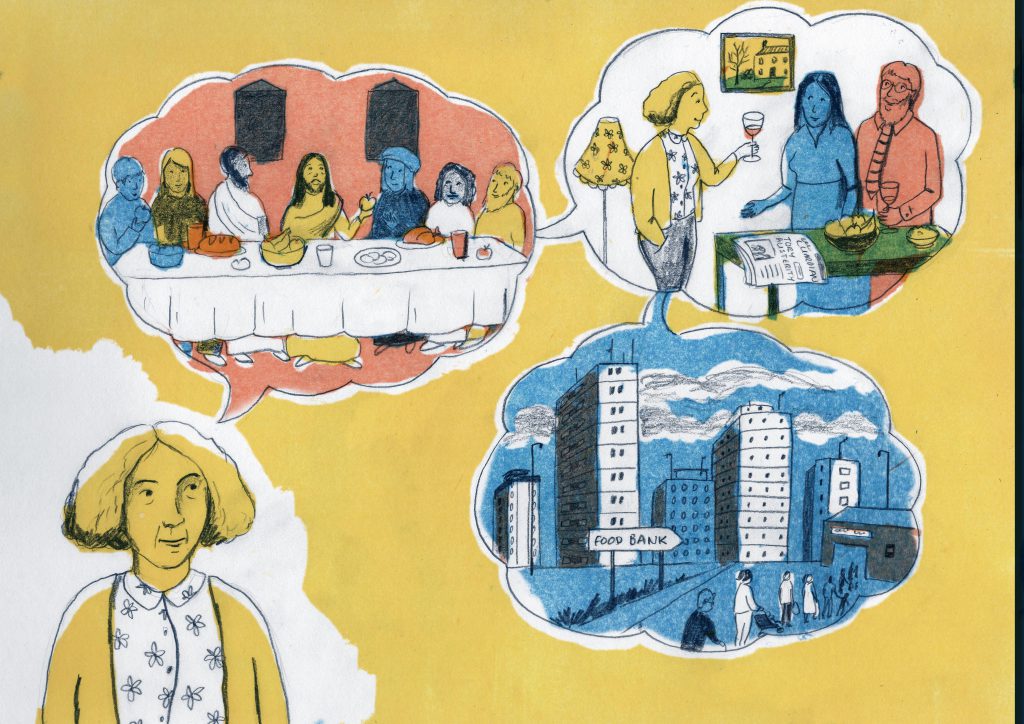

A stereotype of a Christian faith motivation for responding to poverty is often framed in terms of people following the example of Jesus’ teachings, loving your neighbour, and therefore helping people in need. However, reality is often more complex than this, particularly as whilst a project may have an overall ethos, there will be a mix of staff and volunteers who each have their own motivations. The complexity of faith motivations can be drawn out through three different projects that we’ve worked with during the Life on the Breadline research:

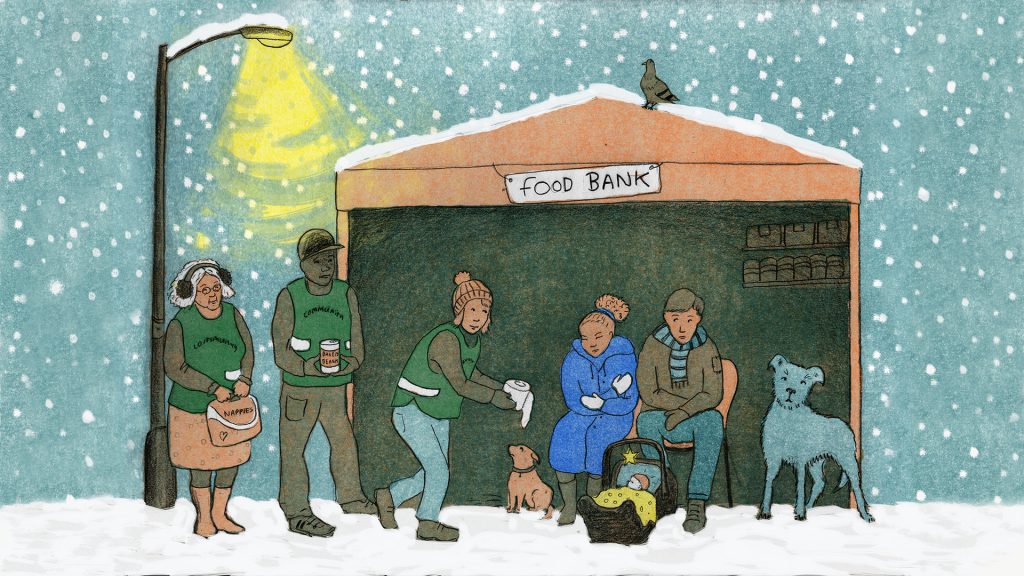

- A Trussell Trust foodbank which ran with a Christian ethos in a church, but often had more non-Christian volunteers than Christian volunteers. The foodbank ethos aimed to be non-judgemental of people’s circumstances and was described by a foodbank volunteer (who was not Christian) as “true Christianity in operation”.

- A Real Junk Food Kitchen project in Hodge Hill, Birmingham. Hodge Hill Church and partner organisations on the estate including Open Door work through asset-based community development which prioritises being with and not doing to a community. Whilst the kitchen was a chance for people to cook together and eat a cheap meal, it was also about so much more than food – about relationships and community building.

- A food pantry run through Church Action on Poverty. Food pantries offer a different solution to chronic poverty than foodbanks, with a pantry volunteer describing it as “a place to build positive relationships” as they ran it similar to a coffee morning resulting in “Kind of like a glimpse into what the Kingdom of God could kind of look like on earth.”

Overall, we therefore cannot generalise about a single faith motivation, faith can be implicit in actions rather than explicit, being a neighbour is not necessarily serving, and responses to food poverty are not always simply about food.

Practices

Reflections from Maddy:

My thoughts and conclusions stem from work I did with small groups of Pakistani Muslim women in Bradford and Huddersfield in recent years. All the women I spoke with lived in deprived areas of these two cities and were themselves in low income households. I talked to them, not about food insecurity specifically, but about their experiences of food more broadly in contexts of poverty.

Well-established family networks were central to the maintenance of food security within the households of the women I spoke to: family members shared food and caring responsibilities as a matter of course. But food was also commonly shared with neighbours, and it was shared without the expectation of reciprocation – although food was indeed regularly reciprocated. Some of the women described the religious underpinnings of this reciprocation of food. Food was commonly shared between neighbours during religious festivals, but hospitality and the exchange of food was also considered a central part of Islam, which was itself a ‘way of life’. None of the participants explicitly discussed Zakat – compulsory charity and the third pillar of Islam – or sadahaq, voluntary almsgiving. This is not to say that these religious principles did not inform their food redistribution but it was notable that the conversations I had with these women in Bradford and in Huddersfield echoed other – and secular – traditions of mutual aid, as seen in the writings of the 19th century anarcho-communist, Peter Kropotkin. What this highlighted was not necessarily engagement with particular texts or adherence to a specific philosophical school of thought, but the commonality and centrality of mutuality, centred around food, within families and communities.

Political theologies of food justice:

Reflections from Phil:

Unfortunately, while the faith based nature of much of emergency food aid effort clearly demands an urgent theological response and guiding vision, with some notable exceptions along the way, (including Charlie’s very helpful recent book, Bread of Life in Broken Britain), this has largely been, regrettably lacking. More research is needed to better elucidate the Christian identity of the work taking place, and to tackle head on, some of the many tensions and dilemmas necessarily entailed in emergency food aid for the churches.

Following on from the penetrating analysis by Chris Allen in 2015, who identified the theological inadequacies of the two dominant approaches of Christian food aid (food charity and social justice models), I’d like to capitalize on his key point about where we need to start our theological visions from.

As a Christian community, I think we urgently need to ask ourselves, where is the agency, voice and influence, of the recipients of Christian food aid in the forms of provision we have chosen? In their design, governance, funding and implementation decisions? As Pope Francis challenged us, what difference would it make, if, rather than to continuing to treat the poor ‘as part of the landscape’, this crisis time became ‘the moment to see the poor’? If we returned to the drawing board, this time ensuring that we co-built from the actual concrete social context of oppression that food aid recipients are subject to, with dignity, solidarity, subsidiarity, reciprocity and mutuality as our foundations, what radical alternatives could we offer?

Reflections from Charlie:

In the interviews I carried out at County Durham Foodbank, I spoke with one volunteer who told me:

I’ve had multiple people try to justify what kind of person they are and why therefore they deserve their food parcel, which is always something I’ve felt really uncomfortable with. Because my take on it is that they don’t have to come in and justify themselves to me, but I’ve had people completely unprompted say ‘I’m not on drugs, I’ve not done this, I’ve not done that….’

What this volunteer has intuited is a moral element to the distribution of resources in society. Proof of virtue is related to the perception of whether one deserves to eat.

Martin Konings, a contemporary political theorist, talks about this, situating it in capitalism’s ‘emotional logic’ and ‘ethical appeal’. Using Koning’s work, my presentation suggested that it is only in analysing moral arguments based on emotional appeals repeated as articles of faith that is it possible to understand how austerity politics held, or continues to hold?, such traction in the minds of the public and begin the task of rendering redundant the emergency food aid network.

If this analysis is correct, and contrary to popular opinion, the task before the food aid community is understanding how the issues we face stem from moralism not relativism, public emotion not public reason, and theological commitments not secular rationales.

Moving forwards:

Concluding thoughts from Andy:

For a long time now, I have been reflecting on the ethics of care within religious welfare settings, especially homeless services and drug and alcohol treatment. In my involvement running a foodbank centre, I have had to think through some of the dilemmas surrounding religious involvement in food aid. Should prayer be offered in a foodbank, for instance? Do volunteers appreciate the power dynamics involved in the ‘gift exchange’ where the provision of food is met with an unwritten desire or obligation to reciprocate? How does religious faith frame understandings of ‘care’, ‘dignity’ and ‘justice’? Are these espoused values (what we think we are doing) always reflected in the lived experience and encounters within food aid projects, and in the organisational models and funding relationships we draw upon?

This workshop raised a series of important questions to help academics and practitioners reflect on the ambiguity and divergent possibilities surrounding religion and food aid. Participants and panellists shared insights and experiences that disturbed overly simplistic and neat classifications of faith-based responses to food aid. By identifying the ways in which faith motivation connects to a range of practices (e.g. voucher-based / mutual aid), experiences (e.g. stigma / in-commonness) and organisational responses (e.g. franchised / grassroots), we can begin to trace the possibility of a more radical vision of food justice.