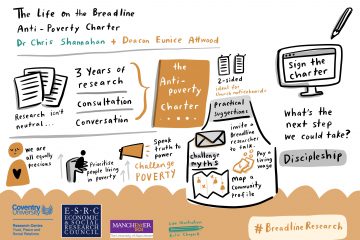

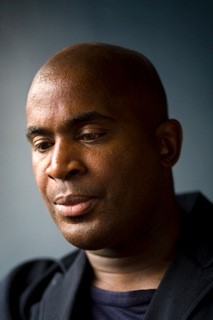

In this blog post our Life on the Breadline Co-Investigator, Robert Beckford, reflects on black churches and austerity in the UK. Robert writes…

Are black churches austerity proof? That is to say, immune from the politics of government austerity? Much depends on what we mean by ‘austerity proof,’ but I will get to this point later. The motivation for contemplating this question arose after making a short film for ‘Life on the Breadline’ exploring the black church’s response to serious youth violence in the context of government austerity. In the narrative of the film, I entangle the subjects of theology, serious youth violence, and austerity to provide multiple ways of thinking about austerity as well as hearing black Christian voices, which are absent from most discussions about austerity.

Let there be no doubt, black communities, primarily African and African Caribbean, are disproportionately brutalised by austerity policies. Research by Unison in 2014 revealed that black public sector workers were more likely to be made redundant than their white counterparts.In the past decade, the living standards of black households fell more dramatically than the national average, with single-headed families with dependent children especially vulnerable to cuts in social spending and changes in benefits and tax credits. Racial inequality in Britain has gone backward, according to the United Nations Special Rapporteur, as a direct result of the racialised application of austerity policies. The intersection of austerity, race, and young people has left black young people especially vulnerable, and according to local councils, the cuts in youth service contributes to the rise in serious youth violence, including knife crime (APPG on Knife Crime, August 2019).

Black churches and Christian leaders have voiced concern and acted to address both austerity and serious youth violence. They have established food banks, provided debt counselling services in churches, and funded para-church groups to work with vulnerable young people. In both cases, however, underlining their actions is the subliminal influence of a conservative Christian behaviouralism.

In his 2001 book, Race Matters, African American philosopher Cornel West distinguishes between two types of response to racialised oppression in black communities. These are conservative behaviouralism and liberal structuralism. The former promotes self-help and personal responsibility, and the latter, demands a change in social policy to address inequality in black communities. In reality, a mixture of both is necessary to secure meaningful resistance, that is, personal resilience and policy change.

For the short film, ‘Swords into Ploughshares: The Churches, Youth Violence and Austerity‘, we interviewed several church-affiliated organisations about their response to serious youth violence in the context of austerity. What struck me was the overwhelming support for practices and interventions which closely align with West’s first category, conservative behaviouralism. In short, these church groups adopted an empowerment approach to serious youth violence that reached out to young people to offer them individual strategies for personal transformation.

While austerity undoubtedly impacts individuals on a personal level, including a lack of public services to support young people, it is a policy promoted by the Conservative government and played-out through policy change, and it has a structural impact on families and communities. Therefore, any meaningful black Christian response to austerity must also deploy West’s second category, liberal structuralism.

The reasons for the failure to adopt the second approach are multiple. Black churches are in the main, Pentecostal denominations with long histories of paying deference to the state, accompanied by a concomitant reluctance to engage in public protest, advocacy, or political theology (Dread and Pentecostal: A Political Theology for the Black Church in Britain, 2000). This perspective does not mean that they ignore the social world; on the contrary, they adopt an alternative strategy rooted in a theology of divine abundance. That is to say; these churches believe that “God will make a way.” In other words, in the context of austerity, the formula for social change is a personal-spiritual, behavioural change rather than a church-based political praxis. And this is what I think makes them austerity proof—a diunitalism of political deference and Pentecostal pneumatology.