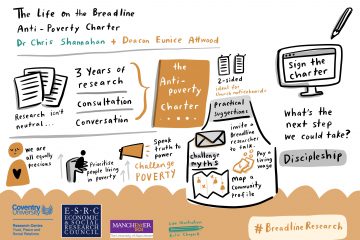

How can voluntary sector responses to food poverty respond in the short-term to people’s need, and work for longer-term change? Are responses a sticking plaster without addressing the causes of food poverty? Life on the Breadline’s Research Fellow, Stephanie Denning, engages with these questions in a paper recently published in the Voluntary Sector Review.

The paper makes use of three principles from a Church Urban Fund report Ingredients for Action, co-authored by Stephanie and Heather Buckingham: being relational, encouraging participation, and working for justice. It does this in the context of a project ‘Lunch’ that Stephanie established and ran to respond to holiday hunger – children not having enough to eat in the school holidays. The paper argues that whilst voluntary sector responses can respond to need in the short-term, the three principles of being relational, encouraging participation and working for justice can facilitate a response that also works for longer-term change, which engages with the state and the causes of food poverty.

The scale and causes of food poverty in the UK

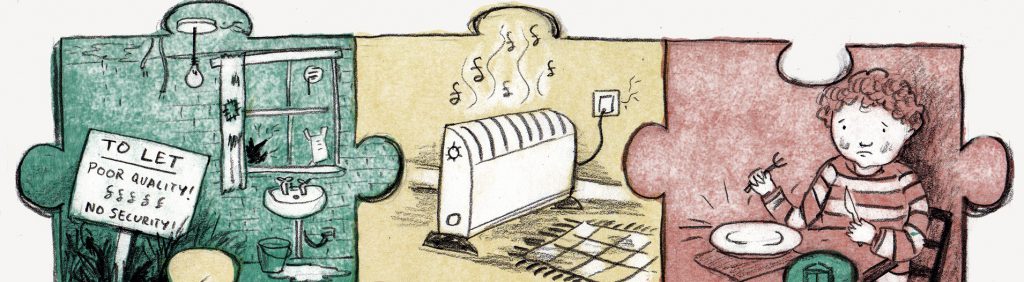

There are an estimated 14 million people in the UK experiencing food poverty, with food poverty being one dimension of poverty. Food poverty is not only about the amount of food eaten – it is also about how nutritional food is, how affordable food is, and how accessible good food is.

Holiday hunger is one aspect of food poverty. Holiday hunger is when a child does not have enough to eat in the school holidays – there are around 3 million children in the UK at risk of holiday hunger.

The causes of food poverty are complex, but evidence from across the voluntary sector and research in the social sciences consistently shows that the causes of the food poverty and predominantly related to changes in the welfare state. Therefore, to respond to food poverty in the longer-term, organisations need to engage with these changes and policymakers.

Holiday hunger case study: reflections on being relational, encouraging participation and working for justice

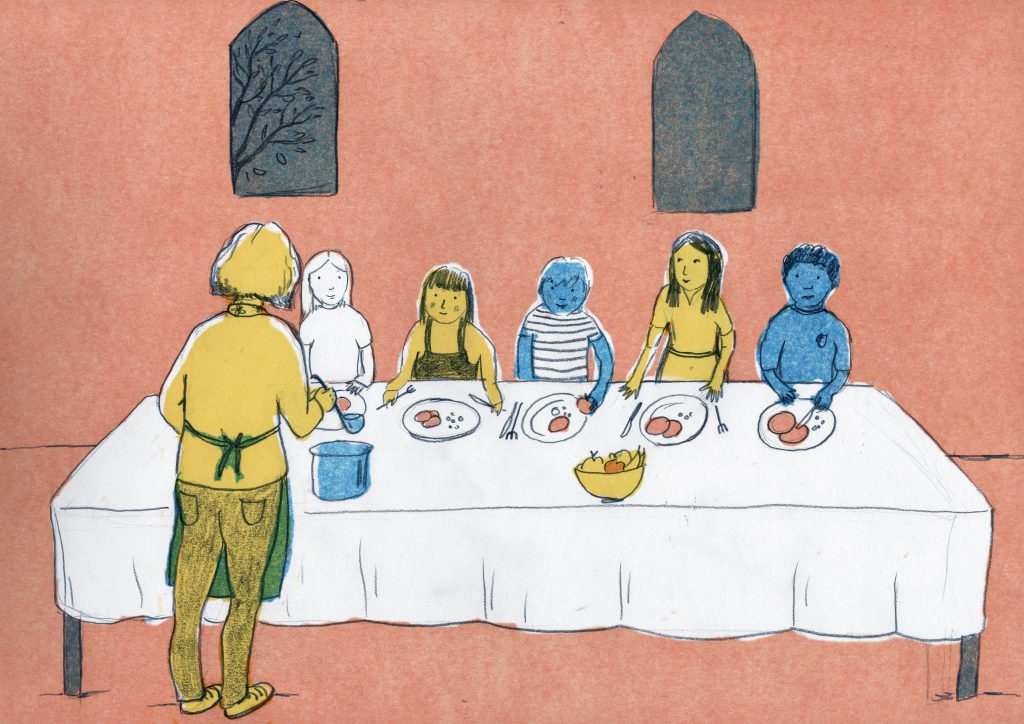

In 2015, I established and ran a project through TLG responding to holiday hunger in an inner-city church where deprivation was in the top 5% nationally. The project ‘Lunch’ gave local primary school aged children a free hot meal and play time, and whilst the majority of volunteers were Christian, there was no religious content for the children. In the paper in the Voluntary Sector Review, I draw on volunteers’ reflections with my own reflections as project leader on how Lunch endeavoured to achieve in practice a voluntary sector response to food poverty that responded in the short term and worked for longer-term change. In this blog post, I summarise these reflections below:

Being relational: Being relational emphasises people’s common humanity. At Lunch, the children and volunteers sat down to eat the meal together, and the project was established in response to identifying need in the community. We changed how food was served at Lunch: from the kitchen hatch to serving from bowls at the tables, in an attempt to make Lunch less transactional and more relational.

Encouraging participation: Lunch volunteers came from across the city to volunteer at Lunch which resulted in volunteers with a variety of backgrounds, ages, and occupations working together. Within appropriate safeguarding, we welcomed volunteers of different capabilities: the Christian ethos of Lunch meant that I endeavoured to value each volunteer for what they could contribute. The relationships between the volunteers and children were also important, and facilitated shared learning of each other’s experiences. With the level of stigma

associated with poverty in the UK, such interactions are important in creating longer-term change in people’s views of each other. Some days activities involved the children with cooking the lunch.

Working for justice: it is unjust that people experience poverty, so it is important to change this in the longer-term as well as the short-term. At Lunch, through TLG we took part in advocacy as well as food provision and provided evidence to Feeding Britain for their Hungry Holidays report and Frank Field’s Meals and Activities Bill in January 2018. This principle was challenging for Lunch because the government’s denial of the link between welfare changes and poverty has slowed change. However, we worked to reduce the potential stigma for children attending Lunch, particularly by not having eligibility criteria to take part.

Recommendations for voluntary sector organisations

The paper concludes with three recommendations for voluntary sector organisations aspiring for short and longer-term change in practice:

- To gather evidence on how your organisation is responding to poverty in the short-term, and submit this to government (for example through APPGs) as evidence for the need of long-term change.

- Develop a 5 year and 10 year organisational strategy. It can be easy to be caught up in the immediate day-to-day problems and responses with the bigger picture being left to one-side. Having a strategy will help with working towards longer-term change and make this become part of the everyday.

- Reflect on the principles of being relational, encouraging participation, and working for justice in your organisational setting. What are the implications of these principles in your setting for short and long-term change?

The full paper is available to read in the Voluntary Sector Review journal, and online with subscription to the journal.