Volunteers are playing a crucial role in responding to UK food poverty. Religious faith can be key in motivating people to volunteer, but how do volunteers persist in volunteering? In my PhD research at the University of Bristol I explored to this question whilst running a TLG MakeLunch project responding to children’s holiday hunger.

Why think about why people persist in volunteering?

Volunteering research has mainly considered what motivates people to volunteer, rather than why they keep on volunteering. If voluntary groups are to be sustainable then how people persist in volunteering also needs to be understood, particularly as voluntary organisations are finding it increasingly difficult to recruit and keep long-term volunteers.

The notion of persistence moves beyond motivation and a more general sense of ‘continuing in volunteering’ to recognise the challenges and deterrents that volunteers can face, and how volunteers reflect on their volunteering experiences. To focus on persistence is not to emphasise the negatives in volunteers’ experiences, but rather emphasises the choice that volunteers have in whether to keep on volunteering or not: persistence emphasises that a person’s commitment to volunteering is never guaranteed.

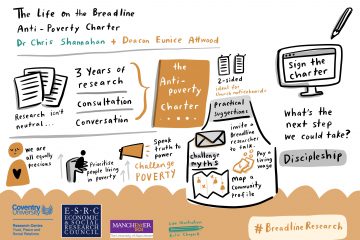

What is shared below is based upon Stephanie’s work published in Social and Cultural Geography.

The MakeLunch project

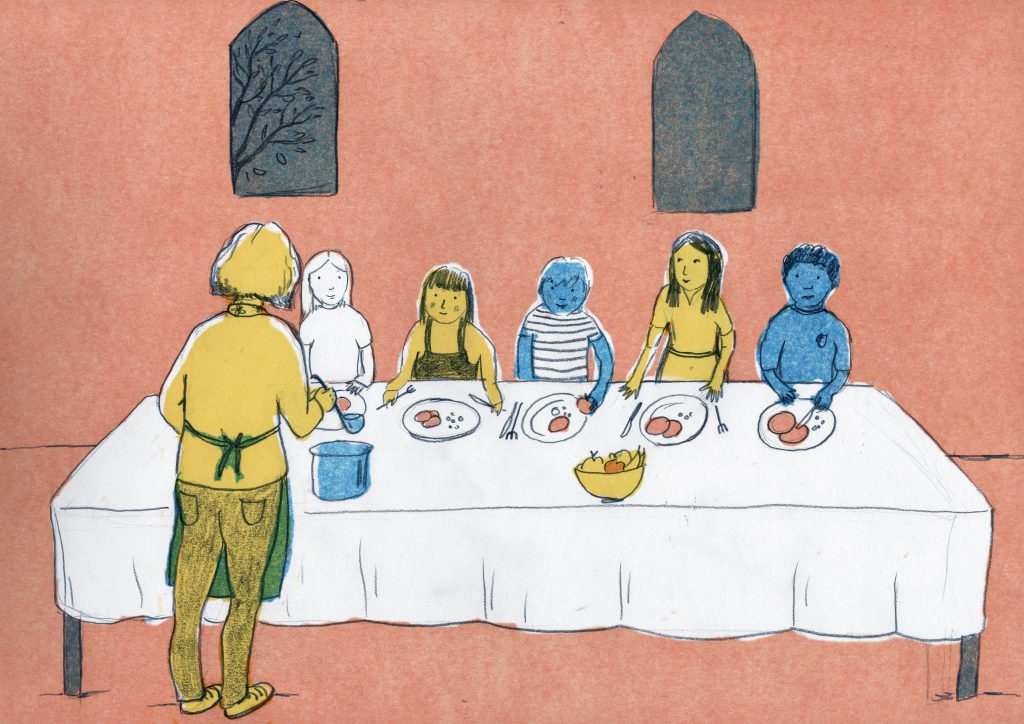

From 2015-2016 I established and ran a MakeLunch project ‘Lunch’ in an inner city church in an area where deprivation was in the top 5% of the UK. The project relied upon volunteers to run and welcomed local primary school aged children for an hour of play, and then a free hot lunch that volunteers and children sat down to eat together. There was no religious content for the children at the project, although the majority of volunteers were Christian. Forty-two of the seventy-eight volunteers participated in the research by writing diaries on their experiences and/or in interviews. Through their own and my own experiences I explored the question of how people persisted in volunteering at Lunch. There were four key themes in volunteers’ persistence (volunteers names below have been changed):

An experience can mean more to volunteers than what is represented in the action of volunteering

Each day at Lunch, volunteers were affected by their expectation of what the experience would entail. This was the case both before their first day volunteering – affected by preconceptions – and afterwards as they and I were affected by previous days at Lunch.

The majority of volunteers were motivated by their Christian faith to volunteer at Lunch. This meant that for some volunteers, the provision of play activities and giving of food held more meaning than what was literally represented by these actions:

“Great to see the children developing – one used a knife and fork for the first time to cut up her own dinner… It felt like family life rather than an institution, and that makes all the difference, I think – a real foretaste of the heavenly banquet.”

Violet, volunteer, diary October 2015

Previously Violet had shared that her motivation to volunteer was both through her Christian faith and political in response to rising food poverty and a desire to challenge people’s perceptions of this. In the diary extract above, Violet reflects on being at Lunch not just as eating together but as “a real foretaste of the heavenly banquet”; to her Christian belief in eternal life. To another person this could have been a secular setting around food, but to Violet the meaning is changed by her Christian faith and in other words how her experiences volunteering are an acting out – a performance – of her faith.

Volunteering impacts volunteers rather than only the ‘recipient’

It can be easy to understand food provision as a ‘giver’ (the volunteer) and a ‘receiver’ (the child who needs food). Indeed, overall the aim of the MakeLunch project was to respond to holiday hunger – to prevent children being hungry in the school holidays. However, volunteers’ diaries and interviews show that they too were affected by their experiences. Emphasising this goes some way to start breaking down the binary of a giver and receiver in volunteering experiences. Benefits that volunteers shared included making new friends (with volunteers and the children), teamwork, a sense of satisfaction, and learning new skills.

“Then the great rewarding moment… in comes Jonah, recognizes me, face lights up, rushes over, grabs the dominoes, calls his friends and away we go… It’s been a delightful experience.”

Tony, volunteer, diary august 2016

In the above extract Tony reflected on how after he had played with a group of boys, they had recognised him the next time that he volunteered and wanted to play again. Tony was one of the eldest volunteers at Lunch, in his 80s, and brought his own set of dominoes to play with the children because he could not kneel on the floor to play the giant floor set.

Fleeting moments are as important as ongoing experiences

What Tony’s extract also shows is how fleeting moments in people’s volunteering experience can be as important as ongoing events for whether they will persist in volunteering – it profoundly mattered to Tony that he had been recognised and such experiences fed into Tony’s desire to continue to volunteer, even as he experienced health problems.

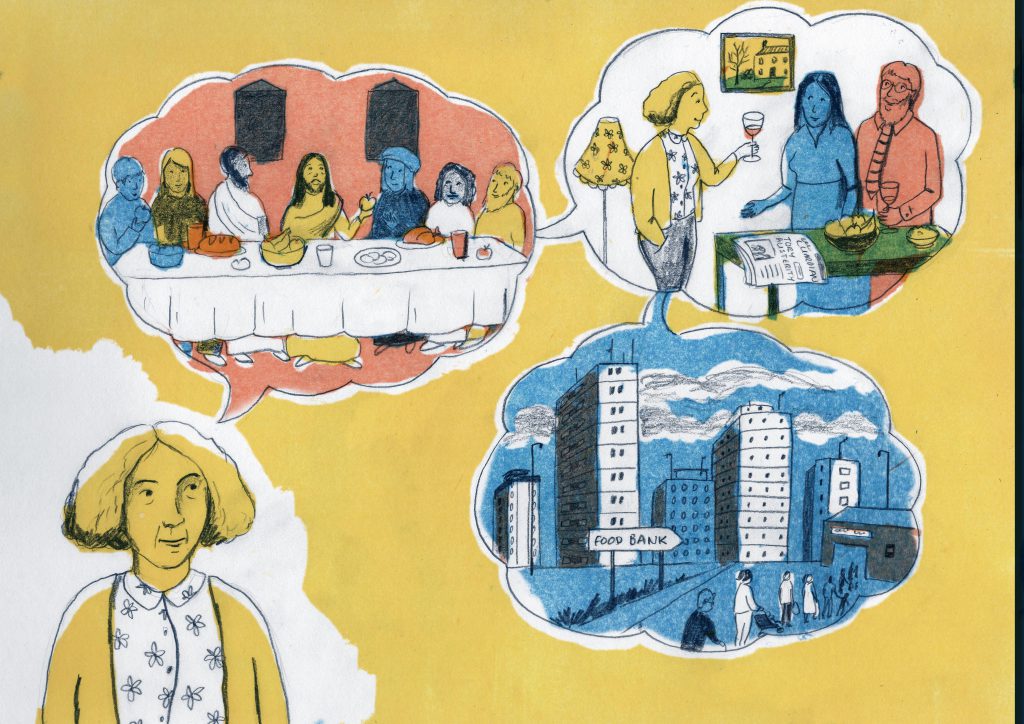

Persistence in volunteering is a continual process of motivation, action and reflection

The previous three themes are brought together in an overall understanding of persistence in volunteering as a continual cycle process of motivation, action and reflection. Different factors from the past, present and anticipated future feed into volunteers’ motivations to continue volunteering or not. Motivation is therefore not simply at the start of a volunteers’ journey, but must be continually reignite if a person is to persist in volunteering.

The findings of this research were used to write a policy briefing on how voluntary sector organisations can retain volunteers. To read more on this topic – including extracts from a wider range of volunteers’ narratives – see the paper Stephanie has recently published in the journal Social and Cultural Geography at

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14649365.2019.1633685 If you don’t have university access to the journal, the first 50 downloads are free or please contact Stephanie at stephanie.denning@coventry.ac.uk